Is it really a good idea for Eminem to precede the release of the inevitably disappointing first single off of his upcoming album with this absolutely insane freestyle? Now people are actually going to be expecting a return to form.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Friday, April 23, 2010

Video Games as Art: A Proposition

At the end of the post I did a month ago on video game addiction, I left an opening for future posts on the subjects of whether gaming is healthy and whether games are art. As it happens, this past week has presented an ideal context to address the second question, as famed film critic Roger Ebert posted a substantive rebuttal to a talk claiming the mantle of art for gaming. Ebert's critique builds off of an earlier exchange on the topic between himself and Clive Barker (yes, the one you're thinking of), and his position is stated boldly in the title of his latest post: video games can never be art. I won't link to any of the responses from gaming press and enthusiasts, but suffice it to say they range from polite engagement to petulant dismissal and none (that I've read) agree with Ebert.

I do agree with him, and I think that it would benefit the status of gaming as a cultural phenomenon immensely if more people immersed in gaming did, too. The essence of Ebert's case against gaming as an art form rests on two related observations. The first, which invokes the tradition of auteur theory in film criticism, notes that video games as an experience are not generally the product of a singular creative vision (i.e. there's no 'artist' whose work one can be said to be taking in while playing a game). The second observation, which is connected to the first one, is that games are ill-suited to producing emotional or intellectual insights about the human condition, which he states most explicitly as part of his 2007 reply to Barker:

The typical response to Ebert from gaming aficionados usually centers on two points: (a) the subjectivity and malleability of how one defines"art" and (b) the fact that gaming is in its relative infancy and no one can tell what the future of the medium will hold. I'm not going to engage these contentions because I find (a) to be tedious and pedantic and (b) to be impossible to discuss in any informed way, because time, not argument, will settle the score.

In fact, in agreeing with Ebert, I'm going to sidestep the particulars of the debate entirely and instead attack the underlying assumption behind it. As a jumping off-point, I want to expand on a point Ebert makes in the closing paragraphs of his most recent post:

This idea regarding the preferability of Improving Ourselves, when filtered through the intense moralistic streak that somehow manages to simultaneously be both one of American culture's greatest strengths and one of it's greatest weaknesses, inevitably comes out as the idea that we should constantly be Improving, and should never consider passing on the opportunity to do so. Ask a gamer if any of these statements sound familiar:

I understand the impulse to go on the defensive and try and stick games with the tag of "art" thus marking them as something with the potential to fulfill the holy task of Improving Ourselves, but it's the wrong path. Instead, I want to see some pushback against this idea that there's a moral obligation to maximizing our exposure to things designed to Improve Ourselves and that we should feel guilty about choosing to do things simply because we find them pleasurable. I want to be clear that this isn't about making different choices - we pretty much wind up doing the things we find pleasurable regardless of how anyone feels about them - but about consciously stating that our choices in entertainment, whether they be video games, watching pornography, or knitting, don't need to be transformative or Important to be worthy of respect. And I think we should get started on this before somebody decides to fuck around and try to make the Un Chien Andalou of games in an attempt to prove Ebert wrong, because I definitely don't want to play that shit.

I do agree with him, and I think that it would benefit the status of gaming as a cultural phenomenon immensely if more people immersed in gaming did, too. The essence of Ebert's case against gaming as an art form rests on two related observations. The first, which invokes the tradition of auteur theory in film criticism, notes that video games as an experience are not generally the product of a singular creative vision (i.e. there's no 'artist' whose work one can be said to be taking in while playing a game). The second observation, which is connected to the first one, is that games are ill-suited to producing emotional or intellectual insights about the human condition, which he states most explicitly as part of his 2007 reply to Barker:

(T)he real question is, do we as their consumers become more or less complex, thoughtful, insightful, witty, empathetic, intelligent, philosophical (and so on) by experiencing them?Ebert openly admits that the vast majority of ostensibly artistic works, including those in his favored medium, fail to clear this bar, but contends that for the reasons summarized above, no video game will ever make the cut.

The typical response to Ebert from gaming aficionados usually centers on two points: (a) the subjectivity and malleability of how one defines"art" and (b) the fact that gaming is in its relative infancy and no one can tell what the future of the medium will hold. I'm not going to engage these contentions because I find (a) to be tedious and pedantic and (b) to be impossible to discuss in any informed way, because time, not argument, will settle the score.

In fact, in agreeing with Ebert, I'm going to sidestep the particulars of the debate entirely and instead attack the underlying assumption behind it. As a jumping off-point, I want to expand on a point Ebert makes in the closing paragraphs of his most recent post:

"Why aren't gamers content to play their games and simply enjoy themselves? They have my blessing, not that they care. Do they require validation? In defending their gaming against parents, spouses, children, partners, co-workers or other critics, do they want to be able to look up from the screen and explain, "I'm studying a great form of art?""To put it simply: pretty much. I'd venture that the average adult hardcore gamer who feels that he (or possibly she, but let's be real about the demographics here) has skin in the "are games art" debate is motivated at least in part by defensiveness over a lifetime of having their enthusiasm dismissed as childish. I think this is more of a human trait rather than something specific to gamers, although male nerds of all stripes seem more susceptible to it - consider the type of person who insists he's reading graphic novels, not comic books. There's a very strong, but mostly unspoken, rule in our culture that things which we do to Improve Ourselves are fundamentally superior to things we do just because we like to. The definition offered by Ebert that I excerpted above pretty much states that art and self-improvement are inseparable from one another, and all semantic debates aside, I think that tracks fairly well with the views of most people.

This idea regarding the preferability of Improving Ourselves, when filtered through the intense moralistic streak that somehow manages to simultaneously be both one of American culture's greatest strengths and one of it's greatest weaknesses, inevitably comes out as the idea that we should constantly be Improving, and should never consider passing on the opportunity to do so. Ask a gamer if any of these statements sound familiar:

"How can you waste the day inside playing video games when it's so beautiful out?"I've played a lot of video games, and barring some sort of thumb incapacitating incident in the near future, I'll probably play a lot more. To answer Ebert's challenge, no video game has given me any sort of experience that has expanded me intellectually, emotionally, or culturally. I am perfectly OK with this, because I never picked up a controller expecting anything like that. I have many other sources of acculturation and learning in my life that more than compensate. What's more: with the time I've spent playing video games, I almost certainly could have learned another language, read more great literature, and cultivated a unique and interesting hobby of some sort. I chose to play video games instead, and I'm not sorry about that. I like playing video games, and that's a good enough reason for me to do it. It ought to be a good enough reason for anybody to do anything in their leisure time.

"Why would you play Guitar Hero when you could be learning how to play real guitar?"

"Why don't you get together with your friends and do something, instead of just playing video games?"

I understand the impulse to go on the defensive and try and stick games with the tag of "art" thus marking them as something with the potential to fulfill the holy task of Improving Ourselves, but it's the wrong path. Instead, I want to see some pushback against this idea that there's a moral obligation to maximizing our exposure to things designed to Improve Ourselves and that we should feel guilty about choosing to do things simply because we find them pleasurable. I want to be clear that this isn't about making different choices - we pretty much wind up doing the things we find pleasurable regardless of how anyone feels about them - but about consciously stating that our choices in entertainment, whether they be video games, watching pornography, or knitting, don't need to be transformative or Important to be worthy of respect. And I think we should get started on this before somebody decides to fuck around and try to make the Un Chien Andalou of games in an attempt to prove Ebert wrong, because I definitely don't want to play that shit.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Rolling Stone's hilariously bipolar cover features

As a longtime subscriber to Rolling Stone who's lost almost all of my interest in actually reading the magazine (it usually winds up on my counter for a few weeks before I manage to even page through it), I'm continually amused by its desperate attempts to simultaneously satisfy its baby boomer audience, who count on it to be the reactionary standard bearer for 60's rock, while trying to woo the young audience, who I assume buy most of the iPod cases that occupy 70% of Rolling Stone's ad space. Basically, the magazine's incredibly half-assed strategy for pulling this off is running cover stories that oscillate between paleo-rock "legends" with no discernable reason for being on the cover of a contemporary music magazine a decade into the new millenium and whatever flash-in-the-pan pop culture phenomenon they can get to pose for a picture and sit for an interview. The main reason I find this entertaining is that I'm fairly convinced that the bulk of Rolling Stone's readership is 60's/70's Lost Causers who need a hit of nitroglycerin to tamp down their angina every time the magazine hits their porch with some teen singer on the cover.

As a demonstration, I present to you the three Rolling Stone covers for the month of April 2010, beginning with the obligatory sop to the boomer base:

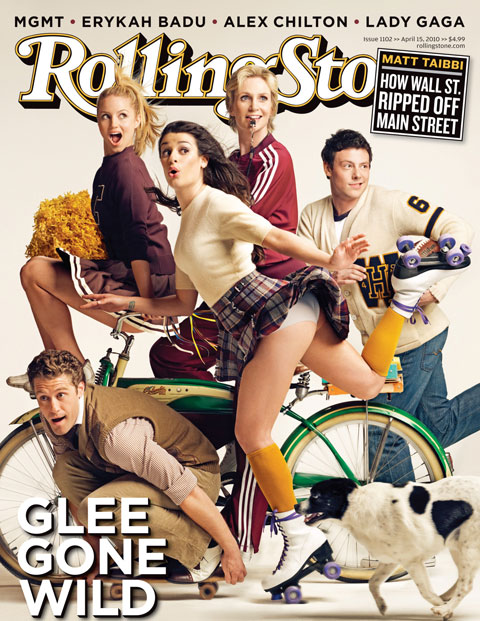

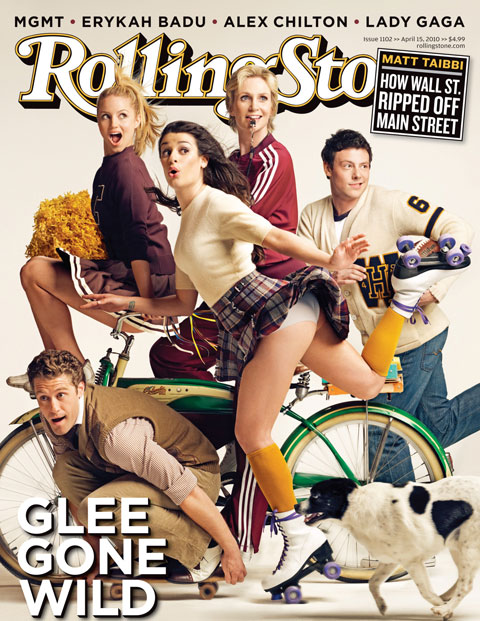

I (obviously) didn't bother to actually read this article, but I assume the latest scuttlebutt on Jimi Hendrix is that he's still dead for 39 years. However, Rolling Stone must have thought that they'd earned major capital with the oldsters on this one, because the cover of the next issue features the cast of motherfucking Glee:

To be honest, I thought Rolling Stone covers had reached their nadir late last year, when they put that Indian kid from the Twilight movies on, but even that has something to do with vampires, which is kind of rock-and-roll if you don't think about it too hard. I'm at a loss for how anybody who works for Rolling Stone could even pretend to care about Glee for any reason other than the potential to sell a few magazines in a shitty economy. And then comes the coup de grâce:

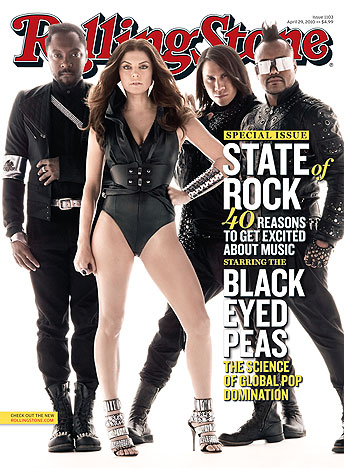

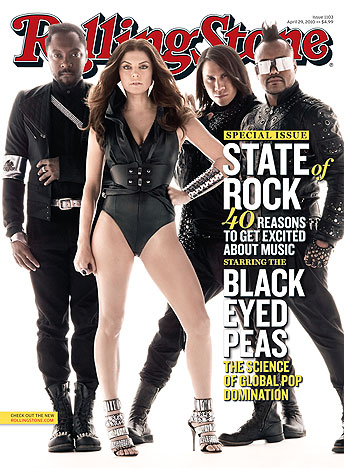

To be honest, I thought Rolling Stone covers had reached their nadir late last year, when they put that Indian kid from the Twilight movies on, but even that has something to do with vampires, which is kind of rock-and-roll if you don't think about it too hard. I'm at a loss for how anybody who works for Rolling Stone could even pretend to care about Glee for any reason other than the potential to sell a few magazines in a shitty economy. And then comes the coup de grâce:

A tip: if you are prepping a piece with the thesis statement that there are 40 reasons to get excited about music, and your first reason involves the Black Eyed Peas, you aren't doing a very good job. In fact, you may have just convinced me to never listen to music again. Enjoy your coronaries, original Woodstock attendees.

A tip: if you are prepping a piece with the thesis statement that there are 40 reasons to get excited about music, and your first reason involves the Black Eyed Peas, you aren't doing a very good job. In fact, you may have just convinced me to never listen to music again. Enjoy your coronaries, original Woodstock attendees.

As a demonstration, I present to you the three Rolling Stone covers for the month of April 2010, beginning with the obligatory sop to the boomer base:

I (obviously) didn't bother to actually read this article, but I assume the latest scuttlebutt on Jimi Hendrix is that he's still dead for 39 years. However, Rolling Stone must have thought that they'd earned major capital with the oldsters on this one, because the cover of the next issue features the cast of motherfucking Glee:

To be honest, I thought Rolling Stone covers had reached their nadir late last year, when they put that Indian kid from the Twilight movies on, but even that has something to do with vampires, which is kind of rock-and-roll if you don't think about it too hard. I'm at a loss for how anybody who works for Rolling Stone could even pretend to care about Glee for any reason other than the potential to sell a few magazines in a shitty economy. And then comes the coup de grâce:

To be honest, I thought Rolling Stone covers had reached their nadir late last year, when they put that Indian kid from the Twilight movies on, but even that has something to do with vampires, which is kind of rock-and-roll if you don't think about it too hard. I'm at a loss for how anybody who works for Rolling Stone could even pretend to care about Glee for any reason other than the potential to sell a few magazines in a shitty economy. And then comes the coup de grâce: A tip: if you are prepping a piece with the thesis statement that there are 40 reasons to get excited about music, and your first reason involves the Black Eyed Peas, you aren't doing a very good job. In fact, you may have just convinced me to never listen to music again. Enjoy your coronaries, original Woodstock attendees.

A tip: if you are prepping a piece with the thesis statement that there are 40 reasons to get excited about music, and your first reason involves the Black Eyed Peas, you aren't doing a very good job. In fact, you may have just convinced me to never listen to music again. Enjoy your coronaries, original Woodstock attendees.

Labels:

black eyed peas,

glee,

icy hand of death,

jimi hendrix,

rolling stone

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Splinter Cell Conviction Micro Kinda-Review

I'm not done playing Splinter Cell Conviction yet, but I'm probably a bit over three quarters through with the single-player campaign. The Splinter Cell series has always occupied sort of a strange space for me: I've bought and played every single one that's been on Xbox/360 (this is the fifth in the series, excluding handheld spinoffs and cellphone de-makes) and enjoyed them all to one degree or another, but it's never been a series that I've felt an abiding passion for to the point where I would consciously identify them as some of my favorites. This is despite the fact that a strong case exists for Splinter Cell Chaos Theory as being one of the most finely crafted games of the previous generation.

Conviction changes up the formula quite a bit: it strips Sam Fisher (the player character) of his government affiliation and gear and puts him in the middle of a revenge tale. The gameplay is a lot different as well; the emphasis is still very much on stealth, but whereas in previous games, killing patrolling enemies was a risk/reward proposition that encouraged you to try to find a way to sneak through undetected, in Conviction you're more or less expected, and often times forced, to shoot most of the bad guys. To the credit of the developers, this doesn't feel like as much of a radical change as it initially sounds - since you're always outgunned and relatively vulnerable, the game isn't structured like a Gears of War/Call of Duty straight-up shooter (with the exception of the fourth level, which is structured exactly like this, and the less about which is said, the better) but rather forces a more tactically aggressive bent while allowing you a fair degree of experimentation.

The centerpiece of this approach is the "mark and execute" system, which allows you to designate between 2-4 hostile targets, depending on your loadout, and hit a button to autotarget and kill them. The catch is that you can only do this after pulling off a hand to hand takedown of another target, so you're forced to use stealth up to get the ability. Since you can mark targets at any time, this creates some really cool scenarios where you can, say, stalk a trio of patrolling enemies from a second-floor vantage point, mark two of them, jump down to take out the third, and immediately nail his companions. The system really allows you to pull off these type of maneuvers in a way that maintains the sense of control while enabling things that wouldn't be possible with previous iterations of the control scheme.

Actually, the controls in Conviction overall deserve high marks. The overhauled system provides some of the most fluid third-person control I've experienced in an action game, with the possible exception of Gears of War, and Conviction is giving you a lot more complexity than does Gears. There are a few snags here and there (I always find myself having trouble getting out of a crouch when I want to run, which requires that you hit RB after leaving cover) but the improvement over previous entries is clear, and obvious care has been taken to make sure that the control scheme fits the new, more aggressive gameplay style.

So I like Conviction quite a bit, which paradoxically makes its flaws and shortcomings more frustrating. The first issue I have with the game is probably more an artifact of my past experience with the franchise, but some of the changes really are at odds with things that were at the core of prior Splinter Cell games, such as the fact that you can't hide bodies anymore and you wind up in situations where you have to shoot your way out with no stealth option. Even the "mark and execute" system, which I think is actually pretty consistent with the Splinter Cell ethos, comes off to me as something that would feel more at home in Max Payne 3 than in a Sam Fisher adventure (note to people making Max Payne 3: steal this idea!)

The second issue I have is with the design choice to make the enemy AI yell at you constantly (nicely skewed in this Penny Arcade strip from last week, which doesn't exaggerate the situation by much). I'm sure there's a solid gameplay rationale for this, because it does improve your ability to track the enemies as they stalk you, but to have supposedly elite combat troops give away their position every five seconds while engaged in a cat-and-mouse battle of tactics really does break the illusion more than is desirable. Finally, despite the promise of a grittier and more emotionally driven narrative, Conviction turns into a boilerplate Tom Clancy improbable-and-poorly-explained conspiracy tales surprisingly quickly, and the dialogue and voice acting, with the exception of the always-great Michael Ironside as Sam Fisher, could use a lot of improvement. Even by the hallowed standards of video games stories, Conviction's plot doesn't make a lot of sense, and the antagonists pretty quickly cross the line into cartoonish supervillainy (word to Waylon Smithers).

I don't know if I'd mark Conviction as a must-buy for people who aren't series stalwarts such as myself, but it's an interesting experiment that does a lot of things rights. I'm really interested to try the co-op mode (the trailer for which I've embedded below), which is a completely different story and set of environments from the single-player and has been highlighted for special praise in a lot of the professional reviews. I could really see how the balance between careful planning and improvisation that the game encourages could be a lot of fun to navigate with another player, and the nature of the gameplay is such that a lot more actual cooperation between players would be necessary as compared to your average shooter. Also, one of the co-op characters is named Archer, which conjures the hilarious FX animated show by the same name. If I get the chance to check this out, maybe my estimation of Conviction will improve.

Conviction changes up the formula quite a bit: it strips Sam Fisher (the player character) of his government affiliation and gear and puts him in the middle of a revenge tale. The gameplay is a lot different as well; the emphasis is still very much on stealth, but whereas in previous games, killing patrolling enemies was a risk/reward proposition that encouraged you to try to find a way to sneak through undetected, in Conviction you're more or less expected, and often times forced, to shoot most of the bad guys. To the credit of the developers, this doesn't feel like as much of a radical change as it initially sounds - since you're always outgunned and relatively vulnerable, the game isn't structured like a Gears of War/Call of Duty straight-up shooter (with the exception of the fourth level, which is structured exactly like this, and the less about which is said, the better) but rather forces a more tactically aggressive bent while allowing you a fair degree of experimentation.

The centerpiece of this approach is the "mark and execute" system, which allows you to designate between 2-4 hostile targets, depending on your loadout, and hit a button to autotarget and kill them. The catch is that you can only do this after pulling off a hand to hand takedown of another target, so you're forced to use stealth up to get the ability. Since you can mark targets at any time, this creates some really cool scenarios where you can, say, stalk a trio of patrolling enemies from a second-floor vantage point, mark two of them, jump down to take out the third, and immediately nail his companions. The system really allows you to pull off these type of maneuvers in a way that maintains the sense of control while enabling things that wouldn't be possible with previous iterations of the control scheme.

Actually, the controls in Conviction overall deserve high marks. The overhauled system provides some of the most fluid third-person control I've experienced in an action game, with the possible exception of Gears of War, and Conviction is giving you a lot more complexity than does Gears. There are a few snags here and there (I always find myself having trouble getting out of a crouch when I want to run, which requires that you hit RB after leaving cover) but the improvement over previous entries is clear, and obvious care has been taken to make sure that the control scheme fits the new, more aggressive gameplay style.

So I like Conviction quite a bit, which paradoxically makes its flaws and shortcomings more frustrating. The first issue I have with the game is probably more an artifact of my past experience with the franchise, but some of the changes really are at odds with things that were at the core of prior Splinter Cell games, such as the fact that you can't hide bodies anymore and you wind up in situations where you have to shoot your way out with no stealth option. Even the "mark and execute" system, which I think is actually pretty consistent with the Splinter Cell ethos, comes off to me as something that would feel more at home in Max Payne 3 than in a Sam Fisher adventure (note to people making Max Payne 3: steal this idea!)

The second issue I have is with the design choice to make the enemy AI yell at you constantly (nicely skewed in this Penny Arcade strip from last week, which doesn't exaggerate the situation by much). I'm sure there's a solid gameplay rationale for this, because it does improve your ability to track the enemies as they stalk you, but to have supposedly elite combat troops give away their position every five seconds while engaged in a cat-and-mouse battle of tactics really does break the illusion more than is desirable. Finally, despite the promise of a grittier and more emotionally driven narrative, Conviction turns into a boilerplate Tom Clancy improbable-and-poorly-explained conspiracy tales surprisingly quickly, and the dialogue and voice acting, with the exception of the always-great Michael Ironside as Sam Fisher, could use a lot of improvement. Even by the hallowed standards of video games stories, Conviction's plot doesn't make a lot of sense, and the antagonists pretty quickly cross the line into cartoonish supervillainy (word to Waylon Smithers).

I don't know if I'd mark Conviction as a must-buy for people who aren't series stalwarts such as myself, but it's an interesting experiment that does a lot of things rights. I'm really interested to try the co-op mode (the trailer for which I've embedded below), which is a completely different story and set of environments from the single-player and has been highlighted for special praise in a lot of the professional reviews. I could really see how the balance between careful planning and improvisation that the game encourages could be a lot of fun to navigate with another player, and the nature of the gameplay is such that a lot more actual cooperation between players would be necessary as compared to your average shooter. Also, one of the co-op characters is named Archer, which conjures the hilarious FX animated show by the same name. If I get the chance to check this out, maybe my estimation of Conviction will improve.

Labels:

game reviews,

gaming,

splinter cell conviction

Sunday, April 18, 2010

Male Studies: A Good Idea That Needs To Be Saved From Itself

As somebody with a dilettante's interest in gender issues, I was pretty interested to hear about the announcement of a new academic discipline called "male studies" last week. The tidbit that particularly caught my attention was the focus on biological differences and their influence on masculinity, which the academics highlighted as a feature distinguishing their vision from that of contemporary academic gender studies. This topic in particular is something that I've been fascinated by ever since I read Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate, a book-length argument for the influence of biology on human behavior that I found extremely compelling and would recommend to anybody.

So the argument that biological differences are insufficiently considered in gender studies is one that I buy completely. In fact, I think a lot of the critical commentary directed toward "male studies" in the blogosphere from writers (presumably) steeped in gender studies goes a long way to proving this point. The main line of argument, typified here by Mother Jones' Titania Kumeh and the Washington City Paper's Amanda Hess, is that Men's Studies already exists and already incorporates biological perspectives. The first point is definitely true: the American Men's Studies Association has a website and a president, who is quoted in the NYT labeling the proposed "Male Studies" discipline "kind of a Glenn Beck approach," which doesn't make any sense taken literally, but can be safely assumed to be an expression of disapproval given the context.

The second point, about biological differences being covered in Men's Studies, seems pretty dubious to me. Here's how the Men's Studies association defines the spectrum of topics covered by the discipline:

What I take this to mean, and I don't think I'm being unfair here because I've heard similar sentiments expressed in the past, is "biological differences may exist, but we're not interested in talking about them because they don't seem to be something that we can influence as easily as social standards." Later in her post, Kumeh fears that teaching about biological differences "lacks context and conscience" and "gives people an excuse not to change." This basic idea, which again I believe to be fairly widespread among gender studies scholars and students, is exactly why we need an disciplined and intellectually serious examination of biological differences. I've never read, in either the popular or scientific press, any argument that social and cultural factors are irrelevant to gender differences.

Instead, most of the discussion (again, I can't recommend Pinker's book strongly enough) centers on the idea that the timeless nature/nurture argument is essentially a false dichotomy and that biology deserves to be considered seriously as a key influence on how and why the social context develops, including gender norms. Again: no credible commentator that I'm aware of on the topic is agitating for the strict "anatomy is destiny" hypothesis, or endorsing the idea that biology excuses discrimination or injustice. There are plenty of populist idiots beating that drum, but I'd argue that makes the case for more education about what biological differences imply and do not imply, not less.

Having said all this, there's a fine line to be walked in making this point, and based on the published accounts, the people behind Male Studies aren't doing a very good job in walking it. In a nutshell: the least productive thing possible in this instance is rhetorical mudslinging directed at feminism, which is exactly what one of the architects behind the discipline, Rutgers anthropologist Lionel Tiger (apparently his real name) does in referring to it as “a well-meaning, highly successful, very colorful denigration of maleness as a force, as a phenomenon.” This is a terrible idea for a very simple reason: "feminism" isn't an easily defined thing. It's a multifaceted and complex tradition that covers a diverse array of political, intellectual, and philosophical questions and features a continually evolving internal debate. I find it extremely unlikely that the Male Studies set categorically opposes all things identified as feminist; for instance, I doubt that Dr. Tiger is agitating for the repeal of women's suffrage or the decriminalization of marital rape. Rather, they're pushing back against one very specific component of some feminist thought: the idea that biological differences should be marginalized in discussions of gender.

Framing this argument as a broadside against the abstract notion of feminism is essentially an invitation to be dismissed summarily by anyone who self-identifies as feminist (if it wasn't for my prior interest in the topic, I would have done so myself). It also opens Male Studies proponents to the ad hominem charge of misogyny, which many gender studies stalwarts are quick to deploy. If the discipline of Male Studies wants to define itself as an antidote to feminism writ large, we can expect the level of rational discourse on both sides to roughly resemble that of an Internet forum debate between fans Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings.

Much as I'd like to believe otherwise, I think this is probably the most likely scenario, which doesn't bode well for Male Studies as an intellectual undertaking. I don't think there's a future for ways of thinking about masculinity that gather steam from anti-feminist grievance (see also the Men's Rights "movement," a disastrous amalgamation of embittered men who claim that their child support payments are evidence of a vast conspiracy against the male gender). I do think that a broader conversation about biology and gender than the one currently taking place in the academic-activist spectrum is welcome and needed. In order to succeed, Male Studies has to figure out how to do the second while avoiding the first.

So the argument that biological differences are insufficiently considered in gender studies is one that I buy completely. In fact, I think a lot of the critical commentary directed toward "male studies" in the blogosphere from writers (presumably) steeped in gender studies goes a long way to proving this point. The main line of argument, typified here by Mother Jones' Titania Kumeh and the Washington City Paper's Amanda Hess, is that Men's Studies already exists and already incorporates biological perspectives. The first point is definitely true: the American Men's Studies Association has a website and a president, who is quoted in the NYT labeling the proposed "Male Studies" discipline "kind of a Glenn Beck approach," which doesn't make any sense taken literally, but can be safely assumed to be an expression of disapproval given the context.

The second point, about biological differences being covered in Men's Studies, seems pretty dubious to me. Here's how the Men's Studies association defines the spectrum of topics covered by the discipline:

"Men’s studies includes scholarly, clinical, and activist endeavors engaging men and masculinities as social-historical-cultural constructions reflexively embedded in the material and bodily realities of men’s and women’s lives."If you didn't understand any of that, good for you! You probably spent your postsecondary education pursuing marketable skills. The gist of it is that Men's Studies looks at the ways society, history, and culture affect the way men understand masculinity. Which is good! All those things are important. Notice, however, that biology doesn't make the cut, which would seem to contradict the argument for the redundancy of Male Studies. Kumeh approvingly states that the Men's Studies curriculum " investigates society's standards for masculinity in men and boys. It covers the effects a hyper-masculine status quo has on the XY-chromosomed among us." Again, no mention of biology, until later in the article (after analogizing the idea of male studies to excluding slavery from history courses, which strikes me as something less than a logical and restrained analysis) when she claims that "(b)iology is covered in men's studies, but not in a vaccum that discredits nature/nurture arguments."

What I take this to mean, and I don't think I'm being unfair here because I've heard similar sentiments expressed in the past, is "biological differences may exist, but we're not interested in talking about them because they don't seem to be something that we can influence as easily as social standards." Later in her post, Kumeh fears that teaching about biological differences "lacks context and conscience" and "gives people an excuse not to change." This basic idea, which again I believe to be fairly widespread among gender studies scholars and students, is exactly why we need an disciplined and intellectually serious examination of biological differences. I've never read, in either the popular or scientific press, any argument that social and cultural factors are irrelevant to gender differences.

Instead, most of the discussion (again, I can't recommend Pinker's book strongly enough) centers on the idea that the timeless nature/nurture argument is essentially a false dichotomy and that biology deserves to be considered seriously as a key influence on how and why the social context develops, including gender norms. Again: no credible commentator that I'm aware of on the topic is agitating for the strict "anatomy is destiny" hypothesis, or endorsing the idea that biology excuses discrimination or injustice. There are plenty of populist idiots beating that drum, but I'd argue that makes the case for more education about what biological differences imply and do not imply, not less.

Having said all this, there's a fine line to be walked in making this point, and based on the published accounts, the people behind Male Studies aren't doing a very good job in walking it. In a nutshell: the least productive thing possible in this instance is rhetorical mudslinging directed at feminism, which is exactly what one of the architects behind the discipline, Rutgers anthropologist Lionel Tiger (apparently his real name) does in referring to it as “a well-meaning, highly successful, very colorful denigration of maleness as a force, as a phenomenon.” This is a terrible idea for a very simple reason: "feminism" isn't an easily defined thing. It's a multifaceted and complex tradition that covers a diverse array of political, intellectual, and philosophical questions and features a continually evolving internal debate. I find it extremely unlikely that the Male Studies set categorically opposes all things identified as feminist; for instance, I doubt that Dr. Tiger is agitating for the repeal of women's suffrage or the decriminalization of marital rape. Rather, they're pushing back against one very specific component of some feminist thought: the idea that biological differences should be marginalized in discussions of gender.

Framing this argument as a broadside against the abstract notion of feminism is essentially an invitation to be dismissed summarily by anyone who self-identifies as feminist (if it wasn't for my prior interest in the topic, I would have done so myself). It also opens Male Studies proponents to the ad hominem charge of misogyny, which many gender studies stalwarts are quick to deploy. If the discipline of Male Studies wants to define itself as an antidote to feminism writ large, we can expect the level of rational discourse on both sides to roughly resemble that of an Internet forum debate between fans Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings.

Much as I'd like to believe otherwise, I think this is probably the most likely scenario, which doesn't bode well for Male Studies as an intellectual undertaking. I don't think there's a future for ways of thinking about masculinity that gather steam from anti-feminist grievance (see also the Men's Rights "movement," a disastrous amalgamation of embittered men who claim that their child support payments are evidence of a vast conspiracy against the male gender). I do think that a broader conversation about biology and gender than the one currently taking place in the academic-activist spectrum is welcome and needed. In order to succeed, Male Studies has to figure out how to do the second while avoiding the first.

Labels:

blustery hoopla,

feminism,

male studies,

masculinity,

steven pinker

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Kick-Ass review (in five brief points)

1. The movie really ought to be named Hit Girl, because she's the real star of the movie. This character will be to Halloween costumes in 2010 what Sarah Palin was in 2008 and Lady Gaga was in 2009.

2. Nicolas Cage kills in this movie. Absolutely destroys. His Adam West cadence when in his Big Daddy costume is a great touch.

3. Against all odds, McLovin continues to have a viable career. Between this and Role Models, he's actually starting to look like a force in comedic supporting roles. Bet the guy who played Napoleon Dynamite is pissed.

4. Mark Strong is the new Sean Bean as far as portraying villains goes. He's got the knack for it. Apparently he's the bad guy in the upcoming Green Lantern movie and he almost played Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men.

5. Apparently it's an ironclad rule that any superhero movie has to incorporate a limp romantic subplot. Even this one, which is almost certainly the hardest R comic book movie to date. Fortunately the film doesn't waste too much time on it, just enough to irritate you.

In conclusion, Kick-Ass, which is the 211th best movie ever made according to the sober film scholars that comprise the readership of imdb, is a lot of fun and definitely worth going out to see. I don't think the combination of extreme gore and playful deconstruction of superhero mythology works 100% of the time, but it's definitely a lot less ponderous than some of the more recent entries in the genre have been. Also, it's funny and the action sequences are very well-done. It'll probably have a long life on DVD, particularly since half the target audience won't be able to sneak it to see it theatrically.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPhone

2. Nicolas Cage kills in this movie. Absolutely destroys. His Adam West cadence when in his Big Daddy costume is a great touch.

3. Against all odds, McLovin continues to have a viable career. Between this and Role Models, he's actually starting to look like a force in comedic supporting roles. Bet the guy who played Napoleon Dynamite is pissed.

4. Mark Strong is the new Sean Bean as far as portraying villains goes. He's got the knack for it. Apparently he's the bad guy in the upcoming Green Lantern movie and he almost played Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men.

5. Apparently it's an ironclad rule that any superhero movie has to incorporate a limp romantic subplot. Even this one, which is almost certainly the hardest R comic book movie to date. Fortunately the film doesn't waste too much time on it, just enough to irritate you.

In conclusion, Kick-Ass, which is the 211th best movie ever made according to the sober film scholars that comprise the readership of imdb, is a lot of fun and definitely worth going out to see. I don't think the combination of extreme gore and playful deconstruction of superhero mythology works 100% of the time, but it's definitely a lot less ponderous than some of the more recent entries in the genre have been. Also, it's funny and the action sequences are very well-done. It'll probably have a long life on DVD, particularly since half the target audience won't be able to sneak it to see it theatrically.

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPhone

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

update: Cage on Cage

Not long after I wrote that post on Nic Cage's late-period career last week, I came across this article, in which Cage talks about his upcoming movies Drive Angry and Some Bullshit About Witches, and in so doing, shines a light into his creative process. About the first:

"Drive Angry I'm doing right now," he said, "which is why I have this Celtic blonde hair. I was gonna shave my head and tattoo my skull with black fire but the producer talked me out of it. So I went blonde. I'm the undead. I've been called up from Hell, because Jonah King, played by Billie Burke, a charlatan satanic cultist, sacrificed my daughter; and I'm called up to get vengeance."Again, let it never be said that Cage coasts through the B-movie roles he takes. Here he's in a movie about a reincarnated damned soul who goes around running people over with a car as if he were Matthew Broderick, and his producer has to convince him to tone it down. As for SBAW, Cage has this to say:

"Season of the Witch is another supernatural movie. As you may have noticed, I enjoy playing supernatural characters – City of Angels, Season of the Witch, Sorcerer's Apprentice, Ghost Rider, and Drive Angry. Because when you play a supernatural character the possibilities are limitless. It's endless what you can do with it, the choices, because it's infinity, right? You're not stuck in some contextual reality, whatever that is. So I can get abstract, get outside of the box, as I like to call it."Translation: somebody's going to get paid for this movie, so it might as well be him. Also, the part of Cage's brain that controls his misunderstanding of quantum physics overlaps with the part that controls his desire for maniacal overacting.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

The Curious Anthropology of Insane Clown Posse

In case you haven't seen it yet, "Miracles," the new Insane Clown Posse video, is posted above. It's getting a serious amount of chatter from the lulz crowd, and deservedly so, because even when judged against the ridiculously low standards of the Insane Clown Posse oeuvre, it's laughably bad. It's basically a mishmash of curse words inserted into a list of things that ICP considers "miracles," none of which are actually miracles, similar to how nothing in Alanis Morissette's "Ironic" is actually ironic. There's also a part where one of the duo talks about hating scientists. Since the video came out a few days again, I'm sure that by now there's twenty thousand blog posts snarking on it, so in the interest of preventing redundancy, I'll forego commentary in lieu of encouraging you to read Daniel O'Brien's hilarious post.

Instead, I want to draw attention to the most fascinating thing about Insane Clown Posse besides the awesome badness of their music: the remarkably robust subculture that the group literally stands at the center of. Unless you know a fan of ICP personally or are atypically immersed in music culture, you've probably never heard any of their music before clicking on that video (or never at all if you didn't click on the video). Hell, I was part of ICP's strongest demographic (socially unpopular Midwestern male teenagers) during the group's brief period of mainstream semi-relevance in the late 90s, and counting "Miracles" I've heard maybe four of their songs in my entire life. ICP is not a major mainstream phenomenon by any stretch of the imagination, and they're one of the most critically reviled musical acts in recent memory, if not of all time.

Despite all this, Insane Clown Posse runs a vertically-integrated media enterprise that between music, concerts, and licensed merchandise, grosses somewhere around 10 million dollars per year. Given the current climate in the music industry, that's an amazing accomplishment. Considering that ICP are regarded as a punchline by the vast majority of people who are even aware of their existence, it's downright miraculous.

Except it's not, because ICP have made their bones the old-fashioned way: by cultivating an intense and personal relationship with their fanbase. If you ever encounter an ICP fan (or a "Juggalo" as they refer to themselves), you'll know it, because they'll probably be wearing an ICP T-shirt. In fact they'll probably have one for every day of the week. Not only that, they'll have a surprisingly large vocabulary of ICP-centric slang words and rituals (should you dare to click through to it, this dictionary website somehow manages to convey all of the irritating, ridiculous, and ignorant aspects of Juggalo mentality within the first 30 seconds of loading it up).

Pretty much every last dollar if ICP's lucrative enterprise comes from this guy and the thousands of other diehards just like him. One of ICP's ventures is "The Gathering of Juggalos," a multi-day yearly music festival headlined by the band and affiliated acts held in a remote state park in Southern Illinois not terribly far from where I went to graduate school. It draws up to 20,000 fans. In 2007, writer Thomas Morton went to the festival and wrote up his experience as an article for Vice, a bit of work which probably stands as the definitive anthropological study of Insane Clown Posse fans to date, not that I have a comprehensive grasp of the alternatives. Anyhow, last fall, Morton wrote a stunning rant decrying the practice of smirking at ICP fans from a great height. In the process, he openly admits how writing the article challenged his preconceptions of his subject, makes a (convincing) case that ICP is the new Grateful Dead, and most importantly, nails down the essence of Insane Clown Posse fandom. Here's the key paragraph of his argument:

As for the big one, the joke about who would voluntarily be into this music and save up to go to this festival and be excited about the helicopter rides and Rowdy Roddy Piper and cheeseburgers, here’s your punchline: Poor midwestern kids from mostly broken homes with absolutely no prospects of material success who even goth and punk kids make fun of.And that's pretty much the crux of it. ICP built an empire by embracing with both arms the exact segment of society that everyone else goes out of their way to avoid or ignore. Think about Abercrombie and Fitch forcing a (very attractive) female employee to sort hangars in the back where customers couldn't see her because she had a prosthetic arm and you get a fairly decent idea of the extremes modern consumer society goes to reinforce prevailing ideas of desirability and success, both as a goal to be achieved and an illusion to be created. The people who wind up in ICP fandom don't have a prayer of fulfilling anyone's conventional idea of those notions, or even making a convincing pretense at it, and they know it. In a lot of cases, they've been told it their entire lives.

And then along comes Insane Clown Posse, themselves none-too-bright burnouts from a city that itself has become a sort of American shorthand for failure (Detroit, if you're wondering) with music that combines the sort of barely articulated rage common to every teenage outcast since time immemorial with a goofy aesthetic that screams "I'm not even trying to impress the cool kids." See, the stupidity of Insane Clown Posse is a feature, not a bug; it means that only the people who see themselves as having nothing to lose in the eyes of society will embrace it. Imagine you fell into that category: would you rather go to a show put on by an up and coming buzz band and stand in a crowd of sneering poseurs who'll go out of their way to find fault with you, or would you rather go to a raucous and profane ICP show filled with people who are just happy to have a place to be accepted? Fuck Bruce Springsteen. Insane Clown Posse are the torchbearers of the real American underclass.

I'm a big, big music fan. I could rattle off a list of dozens of albums that have touched me greatly and, I believe, impacted the course of my life in a tangible way. But truthfully, I don't think any musical artist will ever mean as much to me as Insane Clown Posse does to its ardent fans. So by all means, laugh and gape at the video for "Miracles" (I watched it twice, just to make sure it was real) and any of the other dumbass ICP-related stuff you come across, because there sure as hell isn't any shortage of that.

Just don't wonder so hard about what type of person would like this kind of thing.

Labels:

blustery hoopla,

insane clown posse,

juggalos,

miracles

Sometimes there's so much beauty in the world I feel like I can't take it....

Sunday, April 4, 2010

thesis statement: Nicolas Cage's late period career is fascinating and underappreciated

Above: Nicolas Cage's eyebrows have their own acting coach. (Editor's note: probably not true.)

Above: Nicolas Cage's eyebrows have their own acting coach. (Editor's note: probably not true.)The upcoming release of Kick-Ass, which I'm probably more excited for than any other movie this summer with the possible exception of Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, is as good a time as any to address this topic, which has been percolating in my brain for longer than it's probably healthy to admit. With the possible exception of Robert DeNiro, I can't think of any prolific actor whose career choices have been as widely and openly maligned. For instance: in commemoration of the opening of Knowing last winter, EW's Owen Gleiberman wrote a piece entitled "Nicolas Cage: Artist or Hack?", and Peter Travers wrote a blog-length kvetch about the (indisputably true) fact that Cage's worst movies are also his most financially successful. The standard format for the argument against Nicolas Cage is that he started out as a daring and promising young actor, sold out to blockbuster Hollywood immediately after winning Best Actor in 1995, and has since been cashing checks left and right by lazing his way through uninspired B-movies.

Factually, this analysis is correct. Cage did indeed have a pretty incredible string of roles in the late 80s/early 90s (Raising Arizona, Vampire's Kiss, Wild At Heart and the like), and pretty much immediately went into big-budget action filmmaking after winning the Oscar. Also, a substantial proportion of his movies since that time have been terrible (worst offenders being Ghost Rider and Gone in 60 Seconds, by my reckoning, although there's quite a few I haven't seen). Even so, I'm going to argue that not only has Nicolas Cage not wasted his talent in his post-Oscar work, his career choices make him one of the most interesting actors in the movie business. Let's break this down into a series of simple points.

1. Pretty much all award-winning actors go on to make underwhelming movies.

Let's be honest: most feature-length dramas aren't very good. In fact, most critically praised feature-length dramas aren't even very good. And yet, if an Oscar-winning actor wants to "live up" to his talent in his subsequent role choices, the widespread perception is that acting in dramas is the best way to do so. As a result, most of them follow up award wins with horseshit middlebrow films that everyone pretends to care about for five minutes and promptly forgets. Consider the subsequent films of some of the Best Actor winners since Cage won in '95 for Leaving Las Vegas. Roberto Benigni followed up Life is Beautiful (which, for the record, is a movie I despise) by playing the lead role in Pinocchio (no, really). I don't think we even need to mention Kevin Spacey, but in case you forgot: Pay It Forward, K-Pax, and The Shipping News. Denzel Washington did Antwone Fisher after winning for Training Day. Adrian Brody followed up The Pianist with motherfucking The Village. Even Daniel Day Lewis, who's been in something like three movies his entire career, did that musical remake of 8 1/2 that came out last Christmas after winning for There Will Be Blood.

The idea that Nicolas Cage deprived the world of a plethora of brilliant dramatic performances in order to become the next Sylvester Stallone is bullshit. If you were faced with the choice between making umpteen "respectable" variations on Captain Corelli's Mandolin for the remainder of your career or turning yourself into the most overqualified B-movie star in Hollywood history, which would you pick? Moreover, which would you find more challenging or artistically satisfying? This leads us to point number 2...

2. Nicolas Cage almost always substantially improves the bad movies he's in.

Whatever you can say about the quality of his movie choices (any you can obviously say a lot), Cage can't be accused of misunderstanding the fundamentals of B-movie acting. Take, for instance, Con Air, Cage's second action movie after winning the Oscar, which combines an idiotic premise with thoroughly incompetent direction and yet manages to be fantastically entertaining. The latter fact is almost completely due to the casting choices: along with Cage, the movie features John Malkovich, Ving Rhames, Steve Buscemi, and John Cusack, plus a slew of recognizable B-listers, and gives all of them free reign to chew as much scenery as they like. Although the protagonist is written as a run of the mill action hero, Cage plays him with a stoned stupor and a gleefully over-the-top hillbilly drawl. His Forrest Gump-meets-Steven Seagal performance works because it acknowledges both the underlying ridiculousness of the movie and the need to make it entertaining (the same applies to a lot of the leads in Con Air, especially Malkovich).

I can't think of many Nicolas Cage movies that would have been better if they had starred someone else. In fact, most of them would have been worse. Cage gets a fair amount of shit for his overacting, but it's worth mentioning that very few of the movies to which that criticism applies would be improved in any tangible sense by more subtlety. If you've seen Knowing, try to mentally substitute, say, Johnny Depp in the lead role. Would it have been a more enjoyable movie if it featured Depp's trademark eyebrow raising and muttering instead of Nic Cage's trademark manic gesticulating? A hint: no. It would just have made it boring to watch.

Without question, the most glorious example of Nicolas Cage's willingness to go to excess in support of a work of dubious value is in Neil LaBute's staggeringly unnecessary remake of The Wicker Man. There's a fairly famous YouTube compilation of the most over-the-top moments from the film that I'm not going to link to (assuming it hasn't been removed for copyright violation) because seeing the scenes out of context hardly does justice to the sheer inexplicable craziness of the full film. I think of The Wicker Man remake not as a failed attempt at a coherent filmed narrative, but as a deeply personal collaborative attempt by Nicolas Cage and Neil LaBute to merge their dominant artistic impulses (respectively, barely suppressed emotional extremes and hatred of women) into a single work. In that sense (and none other), it's a complete success as a film. Even if you don't care to submit The Wicker Man to a close reading, you can't go wrong marveling at the ridiculousness of it with some friends over beers, and that's far from low praise in my book.

3. He's also done a surprising amount of legitimately fine work.

Something that often gets overlooked in the discussion about late-period Nicolas Cage is that he's also done a lot of good acting in some really good movies alongside the B-grade action flicks. Adaptation is probably the most widely acknowledged of these, but there are others, like the underrated Matchstick Men and Lord of War, and last year's Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, which is probably the best argument for the artistic value of Cage's manic tendencies to date.

Moreover, it's hard to argue that Cage should have turned down many of the dramatic movies that he's starred in that didn't exactly set the world on fire. I doubt most leading men in Hollywood would pass on opportunities to work with Martin Scorcese, Brian DePalma, or Oliver Stone. Even something like Windtalkers, a World War II movie made back when people were still holding out hope for John Woo's Hollywood career, probably seemed like an acceptable risk.

The real issue with Nicolas Cage circa the past 15 years isn't that he does bad work, or even that the bad work outweighs the good work. Rather, it's that the sheer volume of movies he stars in makes him a difficult actor to pin down. This is an actor so prolific that in the first half of the 2000s, he starred in no less than three separate films entitled "The ______ Man." I don't think Cage's chronic inability to not be making a movie at any given point in time (which is hardly an exaggeration, per his IMDB page, he's averaged three films a year over the past decade) is necessarily a bad thing. It just guarantees that his output is going to be wildly uneven. This year alone he's in the promising-looking Kick-Ass and the promising-sounding The Hungry Rabbit Jumps (it has Guy Pearce and is from the director of the The Bank Job, which I enjoyed.) He's also in this movie, henceforth to be referred to as Some Bullshit About Witches:

So it goes. In 2011, he'll be starring in a 3-D movie called Drive Angry, summarized as "A vengeful father chases after the men who killed his daughter." I can't wait.

Labels:

movies,

nicolas cage,

thesis statement

Friday, April 2, 2010

Public Service Announcement

I recommend that you acquire a copy of The Monitor, by Titus Andronicus, because holy shit this album rules (it's available on eMusic, if you subscribe to that). There's probably no way to describe it that doesn't make it sound terrible (my best attempt would be: a concept album vaguely about the Civil War, but not really, that combines early Bright Eyes-esque lyrics with sprawling instrumental tracks and wraps the whole package in a serious anthemic bent). It's fearless, ambitious stuff, and definitely one of those albums that plays as a cohesive whole rather than just a collection of tracks. A sample:

I recommend that you acquire a copy of The Monitor, by Titus Andronicus, because holy shit this album rules (it's available on eMusic, if you subscribe to that). There's probably no way to describe it that doesn't make it sound terrible (my best attempt would be: a concept album vaguely about the Civil War, but not really, that combines early Bright Eyes-esque lyrics with sprawling instrumental tracks and wraps the whole package in a serious anthemic bent). It's fearless, ambitious stuff, and definitely one of those albums that plays as a cohesive whole rather than just a collection of tracks. A sample:Also, be careful who you marry.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)